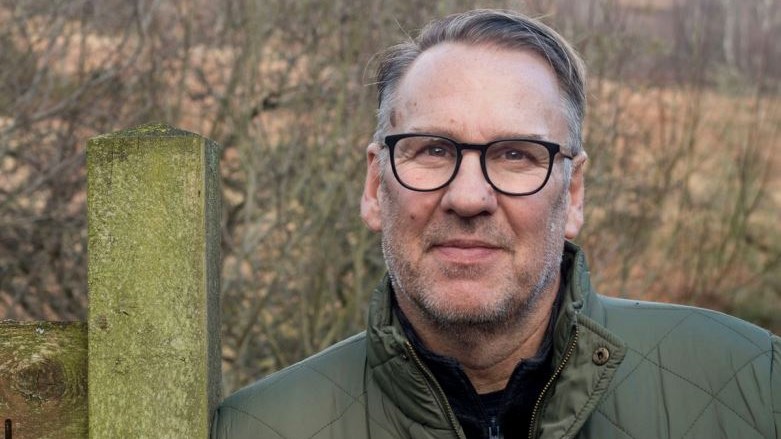

Paul Merson

I was a nervous child, frightened of all sorts of things, absolutely petrified of dogs for one, and sensitive to the stresses of family life caused by money troubles and unemployment. I suffered from separation anxiety. I’d wet the bed a lot and would suck my thumb as a comfort thing past the age of ten.

I was dyslexic, which wasn’t properly dealt with, and also had a speech impediment, so you can imagine how I struggled at school. My mum says I hardly spoke at all before the age of six and she had to take me to speech therapy. Football was a release for me from a young age.

My dad was a good footballer in his youth and had been on QPR’s books after he came out of the army but didn’t get into the first team. He still played on Saturday afternoons and when his mates called for him, I’d get in to a right state, trying to persuade him to stay with me instead. There’d be tears and I’d be upset until he came home. I just loved being in his company, going out with him on his rounds at the weekend and would look for reassurance that he’d be around most nights.

I was very attached to both of my parents, particularly my dad, and I didn’t like being away from him.

In social situations, I wouldn’t say boo to a goose. When I had a girlfriend for the first time, we knocked about together for a month but I never once plucked up the nerve to kiss her. But a couple of drinks brought me out of myself. It completely changed me. I would talk to anybody.

The drink was like boarding a rocket for me, a ticket to a different world. I could be the person who made everyone laugh. If I drank no one would ever know how I was feeling inside.

Alcohol helped me to be the clown, to have a million faces. I could go into a place and people would never know there was something wrong.

I never drank because I liked it. I drank for the effect. Anxiety ate away at me. Looking back, I can’t think specifically what it was that was making me like that because it wasn’t one thing. I was worried about everything all the time. My head was constantly churning with thoughts and doubts.

By the time I was a first-team regular and we would go on tour, one of my party pieces was to run across nightclubs and slide across the dancefloor on my knees, knocking everybody flying out of the way. I would do all kinds of stupid things, just to impress people who were as pissed as I was but had more sense. When you’re shy, you’re insecure and when you do find friends, a worrier will do anything to stay onside.

I started drinking at 15 and by the time I was 22 I knew that one drink was too little and a hundred was never enough.” One drink” would turn into a disaster

I didn’t get hangovers as such, but the lack of a physical reaction to the buckets of beer and brandy I drank when I was out didn’t spare me from the mental reaction, crushing shame and remorse.

Why did I lose all our money? What sort of person would leave a toddler in the car on his own to rush into the bookies? Why was I so moody? Why did I shout at my wife? Why could I put my clown face on at work but be horrible at home? Why couldn’t I stop when those who saw only bits and pieces of what I was doing thought I was pushing it too far? What if they knew everything?

I didn’t see addiction or illness in those frightening moments when I was on my own with only my thoughts, just an evil person looking back at me in the mirror. I had to be no good, I couldn’t imagine any other explanation. That’s what I thought for years. Insecurity and anxiety ate away at me and I blotted them out the best I could, medicating myself with the worst medicine.

I started gambling at sixteen. My first month’s pay packet on the YTS scheme at Arsenal was gone in ten minutes at William Hill. A compulsion to bet has been a constant throughout my adult life. Sometimes I’ve been able to steer clear, but even when I was at my best as a footballer in five alcohol-free years at Villa and Pompey, I was losing millions.

I once won £20,000 and was sitting around my mum and dad’s house that night with the cash, looking and feeling miserable. ‘You’ve won all that money, why are you looking like that?’ my mum asked. ‘Because there’s nothing else to bet on now. It’s finished for the day.’

I’ve been there loads, wanting to kill myself enough times over my gambling, but I kept going back to it. I can see how people go mad.

I did go back. In the first lockdown last year, I lost everything. There were no physical GA (Gamblers Anonymous) meetings and I didn’t look after myself properly. I lost our deposit to buy a house, I lost the lot.

I’d saved and saved since giving up betting the previous year so we could move from renting and get our own home. And it went before I could catch my breath. I couldn’t handle the lockdown, I couldn’t see a way out of despair or fight off the fatalistic feelings. I was thinking, when’s this all going to stop? Are we all going to die?

Everything felt bleak and terrifying, so I did what I had always done to fill my mind with different thoughts. I had a bet, then another and another until I was on the floor.

It’s a cycle and you can only start to get better when you know you are one of hundreds of thousands of people affected by this exhausting illness.

I’ve had long spells of being sober, managed to resist the compulsion to gamble for periods of various lengths and have gone nearly three decades without wanting to go anywhere near cocaine, the third addictive illness which brought me to my knees in barely ten months in 1994. Coke took me to the brink of madness and I’m certain, if I’d carried on, that I wouldn’t be here now.

I exposed myself to all sorts of danger to get it (cocaine), hanging out with drug buddies I barely knew and dealers, running up debts with them and laying myself open to being ripped off, beaten up or blackmailed

I’ve lost millions and millions of pounds to the bookies, lost houses, blown my entire pension and almost destroyed my self-respect. But I’ve been off the booze for more than two years and not had a bet for a year. The fog in my mind is finally clearing.

The longer I’m sober, the more clearly I see and think.

We hosted a barbecue last summer. Nothing special in that, is there? But it was for me because at the age of fifty-two it was something I’d never done before. I was the bloke who went to other people’s barbecues. I would have a laugh and a good drink all afternoon and way beyond, knocking back bottle after bottle long after most people had left, having batted off God knows how many requests from my wife to call it a night. Once I’d started drinking, I didn’t know how to stop.

Now I’m manning the grill. All I’ve wanted my entire life is to be normal – take the kids to the park, sit in the garden, Sunday roast – and be someone my family could rely on. Normality is the ultimate for me. And every day I’m getting there.

Some days are still hard, but now I recognise they’re really no different to anyone else’s bad days. I’m not that special. Every morning, I have a little quiet time to think and pray for patience and for my selfishness not to affect me today. At night, I go to bed, put my head on the pillow, and appreciate that it’s a miracle that I haven’t had a bet or drink. It might sound extreme but after thirty-seven years of living with my addictive personality, it’s not. It’s a miracle.

We only get today and when I keep it in today I am well. It really is a day at a time. When I get up in the morning and say to myself I'm not going to have a drink, drug, or gamble today, it's doable. I try to keep it simple. Football allowed me to live in the present, off the pitch is where my mind would run riot.

Connection is the main one for me. My addiction doesn't want me to talk to my sponsor, or people or attend a meeting.

Daniel (Recoverlution’s founder) approached me about Recoverlution and the most important thing for me is having somewhere I can connect with like-minded others 24/7. My addiction is 24/7 and so my recovery has to be. With Recoverlution, I can connect with others around the world, even if something is troubling me whilst those around me are asleep. That to me is invaluable.